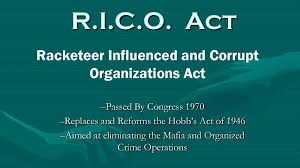

The Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organization Act (RICO) was passed by Congress with the declared purpose of seeking to eradicate organized crime in the United States.

The Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organization Act (RICO) was passed by Congress with the declared purpose of seeking to eradicate organized crime in the United States.

It was enacted as Title IX of the Organized Crime Control Act of 1970, and signed into law by Richard M. Nixon. While its original use in the 1970s was to prosecute the Mafia as well as others who were actively engaged in organized crime, its later application has been more widespread.

Beginning in 1972, 33 states adopted state RICO laws to be able to prosecute similar conduct.

A more expansive view holds that in order to be found guilty of violating the RICO statute, the government must prove beyond a reasonable doubt: (1) that an enterprise existed; (2) that the enterprise affected interstate commerce; (3) that the defendant was associated with or employed by the enterprise; (4) that the defendant engaged in a pattern of racketeering activity; and (5) that the defendant conducted or participated in the conduct of the enterprise through that pattern of racketeering activity through the commission of at least two acts of racketeering activity as set forth in the indictment.

An “enterprise” is defined as including any individual, partnership, corporation, association, or other legal entity, and any union or group of individuals associated in fact although not a legal entity.

“Pattern of racketeering activity” requires at least two acts of racketeering activity committed within ten years of each other.

The civil action for RICO is defined in 18 U.S.C.A. § 1964 (c): “Any person injured in his business or property by reason of a violation of section 1962 of this chapter may . . . recover threefold the damages he sustains and the cost of the suit, including a reasonable attorney’s fee . . . .” Section 1962 has four subparts and generally prohibits the use of income obtained from a pattern of racketeering activity or through collection of an unlawful debt to purchase, establish, operate, or participate in the affairs of any enterprise in interstate or foreign commerce. Because of the vagueness of this language, courts continue to struggle with its interpretation.

Florida’s RICO Act mirrors the federal RICO Act. To be convicted for a violation of the state RICO Act, the defendant must have been arrested because he or she was associated with an enterprise, he or she directly or indirectly was part of the enterprise as evidenced by participating in a minimum of two acts of racketeering activity and at least two of the acts of racketeering activities had commonalities. Potential commonalities include the same or similar victims, co-conspirators, methods of commission, intent, results or other characteristics that established a pattern.

Racketeering activities include the commission, attempt to commit, conspiracy to commit, solicitation to commit, coercion to commit or the intimidation of another individual to commit certain activities specified under Florida law. Racketeering charges may still result and be successful even when the prosecution cannot establish financial motivation that led to the activity. The central focus of a RICO charge is on the individual’s participation in an existing criminal enterprise and how his or her acts contribute to the sustainability of this enterprise.

The RICO Act, both state and federal, have been instrumental tools in fighting organized crime as well as criminal enterprises. Across the country, RICO has been applied to a wide variety of cases including the Catholic Church.