It’s not a smart thing to do, but it’s constitutionally protected. Flipping off a cop is protected under the 1st Amendment to the Constitution. The issue arose after a traffic dispute resulted in a motorist flipping off a police officer and getting stopped a second time. That question, plucked from everyday life in the town of Taylor, Michigan, confronted the U.S.Court of Appeals for the 6th Circuit in the case of Debra Lee Cruise-Gulyas v. Matthew Wayne Minard, in which Cruise-Gulyas was the motorist and Minard the cop.

It’s not a smart thing to do, but it’s constitutionally protected. Flipping off a cop is protected under the 1st Amendment to the Constitution. The issue arose after a traffic dispute resulted in a motorist flipping off a police officer and getting stopped a second time. That question, plucked from everyday life in the town of Taylor, Michigan, confronted the U.S.Court of Appeals for the 6th Circuit in the case of Debra Lee Cruise-Gulyas v. Matthew Wayne Minard, in which Cruise-Gulyas was the motorist and Minard the cop.

Minard went to the appeals court claiming immunity from the suit, arguing that even if he did violate her rights, which he did not admit to doing, those rights were not clearly established.

Judge Jeffrey Sutton, writing for a unanimous three-judge panel Wednesday, disagreed.

While suggesting the woman was a bit “ungrateful,” the second stop was not reasonable and the officer should have known it, Sutton said.

To justify the second stop, he wrote, Minard needed “probable cause that she had committed” a violation.

He didn’t have it, the judge said. Giving the finger is not a crime. That “all too familiar gesture,” as he put it, is “protected by the First Amendment.”

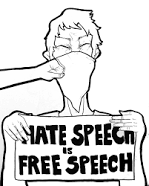

Free speech is a cherished right that’s been constitutionally protected since the birth of our nation. Freedom of speech includes the right:

- Not to speak (specifically, the right not to salute the flag).

West Virginia Board of Education v. Barnette, 319 U.S. 624 (1943). - Of students to wear black armbands to school to protest a war (“Students do not shed their constitutional rights at the schoolhouse gate.”).

Tinker v. Des Moines, 393 U.S. 503 (1969). - To use certain offensive words and phrases to convey political messages.

Cohen v. California, 403 U.S. 15 (1971). - To contribute money (under certain circumstances) to political campaigns.

Buckley v. Valeo, 424 U.S. 1 (1976). - To advertise commercial products and professional services (with some restrictions).

Virginia Board of Pharmacy v. Virginia Consumer Council, 425 U.S. 748 (1976); Bates v. State Bar of Arizona, 433 U.S. 350 (1977). - To engage in symbolic speech, (e.g., burning the flag in protest).

Texas v. Johnson, 491 U.S. 397 (1989); United States v. Eichman, 496 U.S. 310 (1990).

Freedom of speech does not include the right:

- To incite actions that would harm others (e.g., “Shouting ‘fire’ in a crowded theater.”).

Schenck v. United States, 249 U.S. 47 (1919). - To make or distribute obscene materials.

Roth v. United States, 354 U.S. 476 (1957). - To burn draft cards as an anti-war protest.

United States v. O’Brien, 391 U.S. 367 (1968). - To permit students to print articles in a school newspaper over the objections of the school administration.

Hazelwood School District v. Kuhlmeier, 484 U.S. 260 (1988). - Of students to make an obscene speech at a school-sponsored event.

Bethel School District #43 v. Fraser, 478 U.S. 675 (1986). - Of students to advocate illegal drug use at a school-sponsored event.

Morse v. Frederick, __ U.S. __ (2007).

However, as is clear in this recent Michigan case, a right to free speech doesn’t mean it’s always prudent to exercise that right. It’s not a smart idea to flip off a cop. It may be protected speech but you may find you’re pissing on a live wire.