For those who were born after the 1970’s it’s probably hard to imagine that for 190 years our country existed without those suspected of criminal activity to be read their legal rights. Most of us have scene enough police dramas in the movies and on tv to know that a suspect in a criminal case has to be read his rights or any case against him or her can be thrown out by a judge. Yet, up until 1966, that was not the case in the United States.

For those who were born after the 1970’s it’s probably hard to imagine that for 190 years our country existed without those suspected of criminal activity to be read their legal rights. Most of us have scene enough police dramas in the movies and on tv to know that a suspect in a criminal case has to be read his rights or any case against him or her can be thrown out by a judge. Yet, up until 1966, that was not the case in the United States.

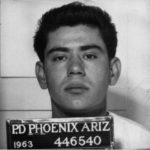

U.S. Supreme Court case Miranda v. Arizona made it a legal requirement for detained criminal suspects to be informed of their legal rights to an attorney and a right to avoid self-incrimination. The case began with the 1963 arrest of Phoenix resident Ernesto Miranda, who was charged with rape, kidnapping, and robbery. At trial, the prosecution’s case consisted solely of his confession. Miranda was convicted of both rape and kidnapping and sentenced to 20 to 30 years in prison. He appealed to the Arizona Supreme Court, claiming that the police had unconstitutionally obtained his confession. The court disagreed, however, and upheld the conviction. Miranda appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court, which reviewed the case in 1966.

The Supreme Court, in a 5-4 decision written by Chief Justice Earl Warren, ruled that the prosecution could not introduce Miranda’s confession as evidence in a criminal trial because the police had failed to first inform Miranda of his right to an attorney and against self-incrimination. The police duty to give these warnings is compelled by the Constitution’s Fifth Amendment, which gives a criminal suspect the right to refuse “to be a witness against himself,” and Sixth Amendment, which guarantees criminal defendants the right to an attorney.

It is considered a landmark case in this country’s history of jurisprudence and safeguards the rights of everyone stopped or detained by the police.

You may know from television or movies that Miranda rights go, more or less, as follows:

You have the right to remain silent.

If you give up your right to remain silent, anything you say, can and will be used against you in a court of law.

You have the right to have an attorney present.

If you cannot afford an attorney, one will be appointed to represent you.

The law does not require that the officer read or tell you about these rights in these exact words. But the officer must still inform you of each of these rights in a way that is clear, accurate, and understandable. And before asking you any questions, he must obtain a clear indication from you that you understand these rights. This means that if you don’t speak or understand English, you must be Mirandized in the language which you understand.

Now, Miranda doesn’t apply every time you have a conversation with a law enforcement officer. There are certain conditions which apply that make Miranda applicable. First, you must be detained (not free to leave) by the police and second, you must be questioned that is done in such a way as to elicit an incriminating response (eg. “Yeah, I have pot in the car”).

In Florida, the police can only stop someone if they have a reasonable suspicion of illegal activity. It’s the police’s job to get you to make an incriminating statement that implicates you in criminal activity. Miranda gives all of us legal protection from over zealous police activity but it is also an important lesson in what to do if you are detained by the police: 1)Shut up and remain silent-the Supreme Court tells you it is perfectly legal. Do it for your own good. 2)Hire an experienced criminal defense attorney who will determine if you were Mirandized properly, among many other things.